A Training School For Elephants

"What an incredible, improbable story this is... a beautiful, intelligent and heartfelt book, a brilliantly researched account of an imperial fever dream alongside a no less feverish contemporary journey. It will haunt me."

— Sunday Times —

A Training School for Elephants became an Sunday Times bestseller, and was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing. The Financial Times named it as one of its Best Books of 2025.

Forthcoming foreign languages editions include Spanish (Planeta, trans. Ramón Buenaventura), Danish (Atlanten, trans. Noa Hansen), German (Zsolnay Verlag, trans. Brigitte Hilzensauer), Dutch (Lanooo), Italian (Settecolori), and Portuguese (Infinito Particular).

The book has been widely reviewed in the UK, US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. It has been featured on BBC Radio, PBS, and the Times Literary Supplement podcast, among others.

"In Roberts’s artful telling, the folly and brute madness of subjugating the African elephant serves as a searing symbol for the conquest of the continent itself. It’s a tour de force."

— Publishers Weekly, starred review —

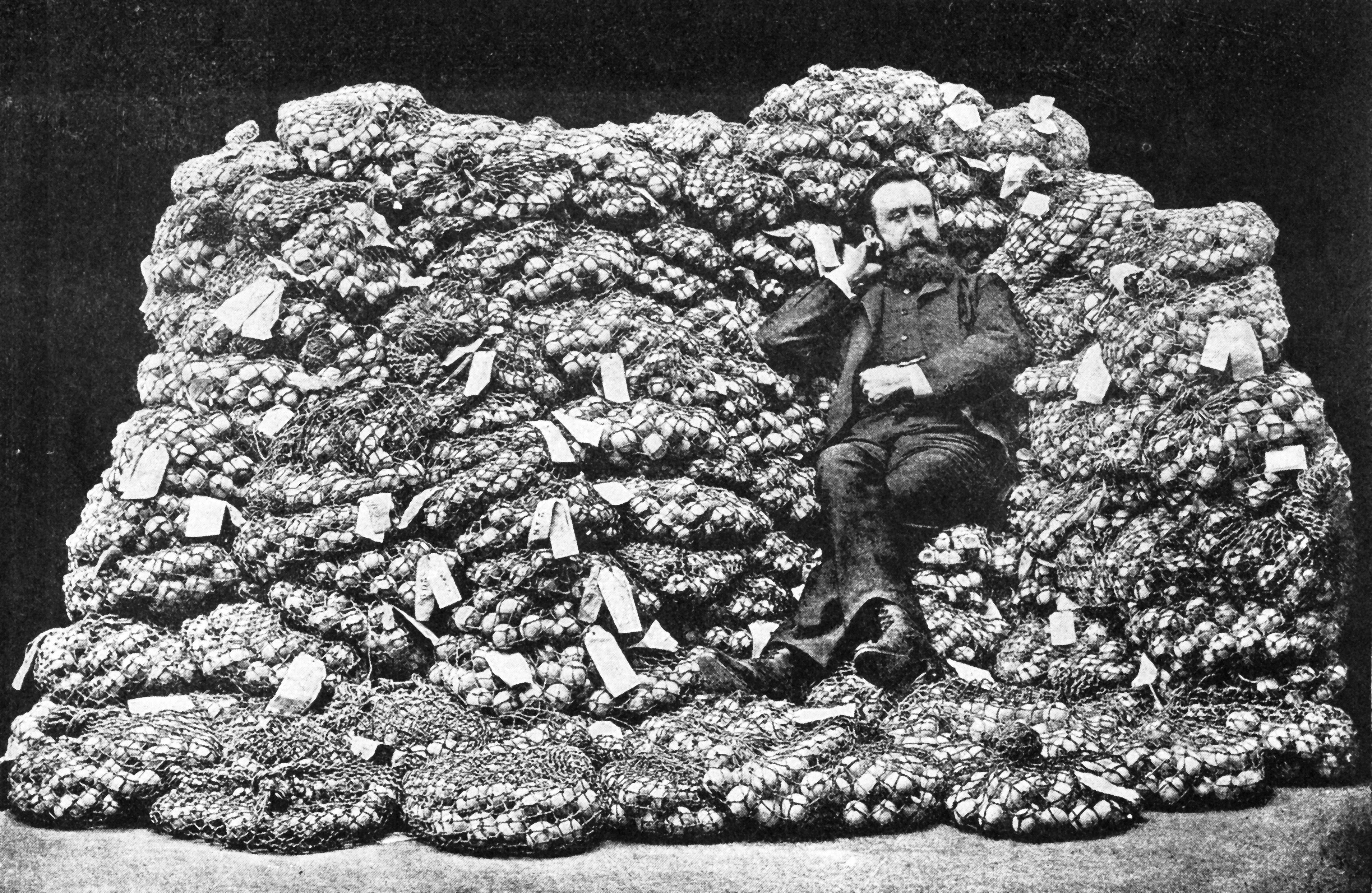

The story is tethered to an 1879 expedition to Africa commissioned by King Leopold II of Belgium. Four Asian elephants were shipped from India to Dar es Salaam, then marched inland towards Congo.

Leopold wanted to establish a training school for taming wild African elephants. He needed a transport system to extract the region's resources, including its ivory, for piano keys, billiard balls and more. Weaving past and present, I follow in the expedition's footsteps to interrogate a forgotten story of cruelty and folly.

The consequences of that little-known elephant expedition are geographically and thematically far-reaching, extending into Belgium, Scotland, Ireland, Iraq, India, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Like my first book, The Lost Pianos of Siberia, I combine history and archive images with travel and contemporary reportage. I bring to life a cast of characters, question what is missing from the stories we inherit, and the gaps in our knowledge and reckonings with the past.

The book features more than 80 black and white images, including rare historic pictures.

MEDIA REVIEWS

"Compulsive... absorbing... rarely has an elegy been so suffused with drama and pathos." — Financial Times

"Luminous… Reflective, watchful, calm, Roberts is such a vivid travel writer that you forget what a brilliant historian she is. She has the water-diviner’s gift for stories in unlikely places. And then, through research in archives as well as on the ground, for uncovering sparky details that bring the story to life." — The Guardian

"A Training School for Elephants works precisely because it is so evocative, and because many of the characters within are more complex – in all their greed and prejudice, but also courage and misguided idealism – than might be fashionable to admit in our censorious times." — TLS

"Top Travel Books of 2025. [A] deft touch underpinned with rigorous archival research. This book sets a new standard in travelogues with multi-strand narratives." — Country Life

"... a master class in the challenges and complexities of contemporary travel writing... Roberts shows enormous sensitivity to her Indigenous sources and to the cultures of ethnic groups in the region, past and present." — Columbia Magazine

"An elegant mixture of history, reportage and travel writing – she has a light touch and never slips into righteous didacticism. Rather, following in the elephants’ footsteps, she discovers that they left an indelible folk memory behind them." — New Statesman

"Roberts writes elegantly and empathetically… part of the book’s power is seeing through her astute eyes the bleak and strange fate of so many magnificent elephants." — The Independent

"Fascinating… a tragic tale and Roberts tells it beautifully… Roberts has produced another wonderful book – a compelling blend of travelogue and history – that marks her out as a singular literary talent." — Literary Review

"Grimly compelling… Roberts tells the story with panache." — Mail on Sunday

"An intriguing tale" — Sydney Morning Herald

Other articles about the book have also been published in Lit Hub, the Financial Times and Airmail.

READER REVIEWS

"Sophy Roberts is the travel writer's travel writer: no one goes further, sees more or listens to a greater diversity of voices. A markedly humble explorer and a penetrating reporter, she uncovers this story in the archives of three continents and pursues it into the remote aftermath of colonialism, finding the people who saw it unfold. A Training School for Elephants is a modern classic: a discovery of history's untold truths, and a glittering telling." — Horatio Clare

"This is a marvellous book, an important footnote to history — of Sophy Roberts' intrepid travel with a real purpose, shining a light on colonialism." — Paul Theroux

"Deeply researched. Brings to life a bizarre and long-forgotten African story with empathy, intriguing encounters and memorable characters, not least the elephants themselves." — Luke Pepera, Motherland

"Superb and sobering. Sophy Roberts' restless curiosity and thoughtful probing makes her a superlative companion in this quest into the heart of Africa in search of colonial folly. An atmospheric travel narrative of the highest order." — Cal Flynn, Islands of Abandonment

"Roberts tackles difficult, sensitive subjects with careful, exquisite prose. Unputdownable."— Mary Harper, Getting Somalia Wrong?

"Such an all encompassing and unclassifiable book. It bridges history, travel writing, natural history with stunning prose. Sophy Roberts has found a tiny story in colonial history and used it to write a masterpiece. She writes about human tragedy, past and present, with such delicacy." — Jaffe & Neale

"An incredible and illuminating tale, wonderfully told, as ever." — Ben Rawlence, Radio Congo

"A cautionary tale from the early days of the Scramble for Africa, but poignant and scholarly too. Roberts writes beautifully." — Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa

"An outstanding book with the level of self-reflection, historical depth and breadth, and nuance that we are always in need of. Do yourself a favour and give it a read." — Tessimo Mahuta, Goodreads

"This is more than an account, it’s a deep dive into the avarice and complexity of colonialism, skilfully guided by a narrator whose words brings to life people, places and actions that have been set aside or glossed over... Few write as compellingly as Roberts, this is her as only she can write." — Amal Chatterjee, Across the Lakes

"A brave and searching book, rich in history and fierce in spirit. The best sort of travel writing: handsome prose, teeming with humanity and an unwavering sense of wonder." — Justin Marozzi, Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood

EVENTS

Upcoming book events, including literary festivals, are published on my author's website.

For event bookings, I can be contated via my agent Sophie Lambert. The book's UK publicist is Sally Wray. The US publicist is Justina Batchelor.

Many of the events feature photography by my colleague, Michael Turek and behind-the-scenes footage of the journey.